Before COVID-19, U.S. Naval War College War Game Examined Epidemic Response

In September 2019, months before COVID-19 became a household term, the U.S. Naval War College co-sponsored a “war” game that looked at how to battle to a rapidly spreading infectious disease in a major urban area.

The lessons of that game, Urban Outbreak 19, now may be more important than ever, as the world’s governments struggle to slow the COVID-19 infection rate.

“We brought some of the very best people who are currently responding to the coronavirus together to play out this scenario before it happened,” said Benjamin Davies, the game’s designer at the Naval War College.

“Now we have a huge data set that allows us to really examine what the experts think they need to be effective in fighting a pandemic,” Davies said.

Some key findings were that nongovernmental organizations were willing to accept higher risk for their personnel than military commands and that local government and local authorities remained the primary agents for a successful response.

Another finding focused on disagreement about the realities of quarantine. While some players viewed forced mass quarantine as an obvious political reality, many medical professionals said that it could drive the infected underground and actually spread the disease faster.

It was instructive to watch the interplay of arguments in the quarantine example, Davies said.

“We had people say that, naturally, we’re going to go into enforced mass quarantine. Other people said, you absolutely shouldn’t for this disease because it will be harder to find the infected,” Davies said. “So now we have different opinions. Does this mean we know whether or not to quarantine? Probably not. But does it mean we’re a little smarter about the things we’re going to face if we do? Yes.”

The other sponsors of the two-day event were the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences-National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health and Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Lab, whose Laurel, Maryland, site hosted the gathering.

“The skill sets and the knowledge were just so diverse – everything from government agencies to the military and the private sector,” said Alexander Soukhanov, a maritime shipping agency executive who played the role of a civilian logistics company owner in the game.

“And it showed that over two days, we could work together. I think that’s No. 1,” he said. “And I say that because, as one of the private-sector people in attendance, time and speed is absolutely No. 1. And in order to respond with time and speed, you have to have relationships and mechanisms in place to plug into.”

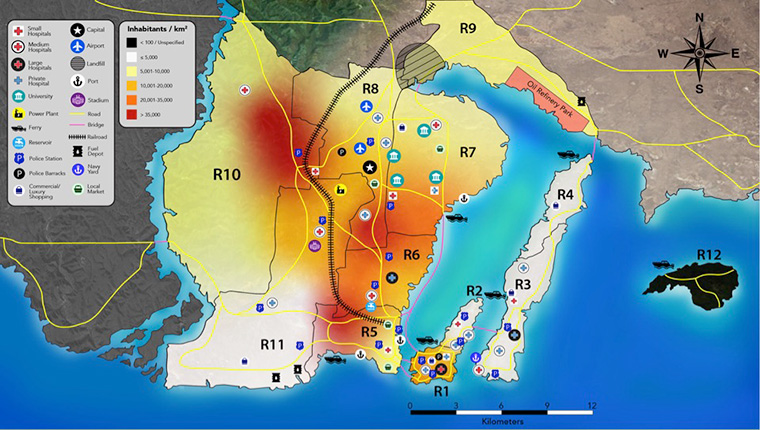

The game’s scenario involved a fictional nation of 21 million people hit by a rapidly spreading disease that can lead to respiratory failure and death. The players were told to coordinate initial and ongoing responses and then a transition to post-crisis conditions.

Urban Outbreak Map

One difference from the COVID-19 crisis is that the game envisioned a multinational response to a serious disease outbreak in a developing country – such as Ebola in parts of Africa – not the current worldwide epidemic.

The participants were 50 people with experience in humanitarian response situations. They came from U.S. and international militaries, humanitarian nongovernmental organizations, the U.S. government, international agencies and the private sector.

Hank Brightman, professor and EMC Informationist Chair in the Naval War College’s Civilian-Military Humanitarian Response Program, noted that the Urban Outbreak game is not predictive of what might happen with COVID-19 or any other health epidemic. However, the issues analyzed in games such as this can be helpful to officials facing real-life decisions.

“War games are informative because you are bringing in groups of stakeholders that then work through decision processes, and those decision processes have value because they are informative to key decision-makers,” said Brightman, who was the game’s lead facilitator and served on the development team.

“As decision-makers look at different courses of actions, they have underlying information that can help them make more informed choices,” he said.

The idea for Urban Outbreak 19 came from a civilian-military humanitarian response workshop hosted at Brown University in 2018. Participants said they wanted a better understanding of the challenges posed by the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa and its 2018 spread in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The results of Urban Outbreak 19 were scheduled to be discussed at a follow-on workshop this month, but the COVID-19 risk forced officials to postpone that gathering until this summer.

“I think it’s safe to say that the desire and expectation is to keep gaming in this arena so we can continue to expand understanding,” Brightman said.

A "quick look" report is available here: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/civmilresponse-program-sims-uo-2019/1/.

Select research and game findings are available here: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/civmilresponse-program-sims-uo-2019/2/.