Bridging the Straits conference focuses on new era of maritime competition

United States defense policy is facing a pivot point as the rise of Chinese and Russian military power means new challenges – particularly at sea, which is considered the most likely theater for conflict.

Academics and military strategists gathered at U.S. Naval War College from Dec. 11-13 to discuss the new landscape for naval power in the Indo-Pacific region as the Navy is in the midst of shaping its future 355-ship fleet.

The “Bridging the Straits: A Research Agenda for a New Era of Maritime Competition” conference aimed to bridge the gap between policymakers and scholars in the conversation about national security strategy, according to organizers Jonathan Caverley and Peter Dombrowski of the college’s Strategic and Operational Research Department.

Officials said the event harkens back to a landmark 1985 Naval War College conference, which provoked a vigorous debate about the Cold War-era maritime strategy that envisioned a 600-ship fleet.

“A very similar event occurred back in the middle of the Cold War to try to understand great-power competition. In that context, the focus was really on a ground campaign in Europe,” Thomas Culora, dean of the Center for Warfare Studies, told the group in his opening remarks.

“This is a very different challenge. This is a near-peer competitor for the Navy and in most ways, naval forces are front and center.”

Speakers included Elbridge Colby, director of the defense program at the Center for a New American Security. Formerly as deputy assistant secretary of defense for strategy and force development, Colby served as lead official in developing the 2018 National Defense Strategy under Defense Secretary James N. Mattis.

“The particular challenge for defense planning in this context is the increased and increasing difficulty of defending the most vulnerable members of our alliance architecture,” Colby said.

“This has become considerably more difficult because the Chinese and the Russians have gone to school on the American way of war,” he said.

“The Chinese and Russians might be able to fight limited wars that would present very serious military challenges to the American military and our allies -- as well as even more difficult political challenges to ejecting (the aggressors) if they secure a ‘fait accompli.’”

Speaker John Mearsheimer, co-director of the Program on International Security Policy at the University of Chicago, put forth the argument that China is the most important competitor by far for the United States -- and particularly for the Navy, as potential flash points, such as the South China Sea, are maritime.

In fact, Mearsheimer argued, Russia isn’t a serious threat to the United States and should be a U.S. ally against China.

“Why we are not working very closely with Russia to get them to join a balancing coalition against China boggles my mind,” he said.

“Russia is a declining great power. It’s not going to get more powerful in time. It’s China that we have to worry about.”

Comparing the United States and the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War, the two nations had roughly the same size population, Mearsheimer said. And, the Soviets had at most a third of the wealth of the United States.

As for China, he said, “We’re talking about a country that in 2050 is going to have close to four times the population of the United States. And, if it turns into a giant South Korea (in terms of economic power,) it’s going to have about two times as much wealth.”

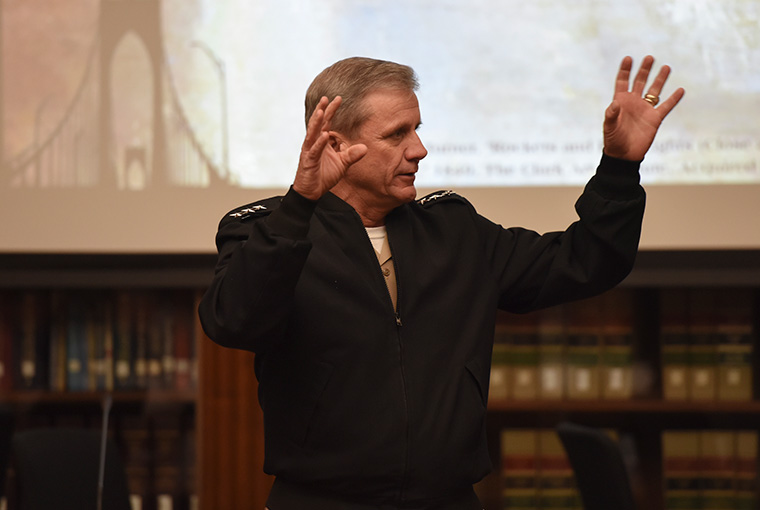

Vice Adm. Richard Brown, commander of U.S. Naval Surface Forces, was the plenary speaker.

Brown -- who oversees training, personnel and equipment for all surface warships and is the leader of the surface warfare officer community -- said this discussion is important in an era of great-power competition.

“Bridging the straits between the academic and policy communities on naval strategy is important,” Brown said, separately from his speech.

“But it is also important to ‘bridge the strait’ between Navy strategy and operational capabilities, so it was an honor to represent the surface Navy today.”