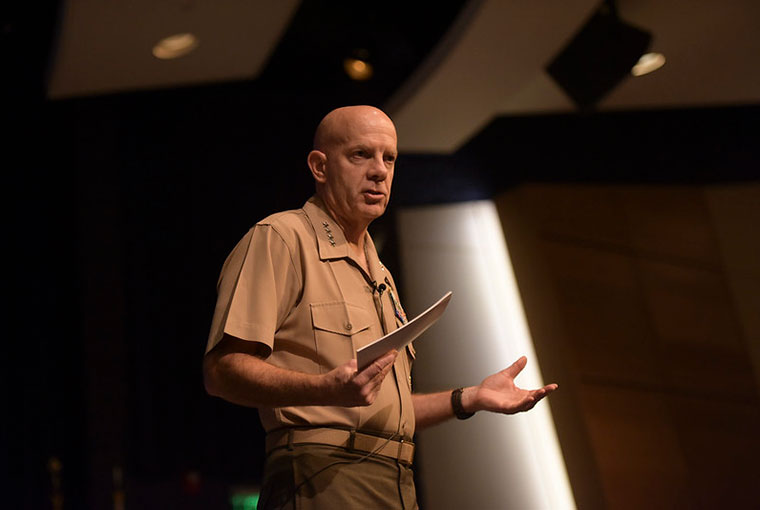

U.S. Marine Commandant Speaks to Students About Future Strategy

NEWPORT, R.I. -- U.S. Marine Corps Commandant Gen. David Berger spoke to the student body of the U.S. Naval War College on Oct. 10, sharing his vision for what the future may hold for the sea services.

“I’m here for two reasons. One, I think I owe you a picture into the future of where I think your naval force and your [U.S.] Marine Corps should go,” Berger said during a speech in Spruance Auditorium.

“The second purpose is for me to listen, because a lot of where I think we need to go is based on some premise, some theory, and I’m asking you to test those theories.”

Berger said he sees the composition and posture of today’s naval forces as a poor fit for the future, which will likely be defined by competition among great-power nations.

The U.S. Marine Corps’ 38th commandant, who took office in July, said he is looking intently at force design, which has not been overhauled in the several decades since the end of the Cold War.

“I’m convinced if we continue to make incremental changes in our [U.S.] Marine Corps, a wider and wider and wider gap will open up between us and our potential adversaries,” he said.

Looking out 10 years, Berger said he sees the U.S. Marine Corps in a threat-informed, concept-driven, capabilities-based landscape.

“You have to understand who your peer threat, your pacing threat, is. You have to have a concept for how you are going to overmatch it, and that drives the capabilities you are going to need in the future,” Berger told his audience.

Berger elaborated on how he looks at the concept of a “pacing threat” in the current competitive environment, and what it means for the United States.

“If you want to set the pace, it’s hard. It’s more expensive. You are going to make more mistakes,” he said. “And yet, intuitively, we want to set the pace. We want to be in front of our pacing threat. As a military, you don’t ever want to behind them.”

The nations in competition with the United States have an easier job, Berger said, if they simply maneuver in reaction to American decisions.

“As a nation, we need to decide if we want to set the pace,” he said. “If we do, there’s a cost to doing that, in terms of money, in terms of research and development.”

Also in terms of force design, Berger said he is thinking more and more about adaptability. One of the ways to become adaptable, he said, is to have an intellectual understanding of the big picture – something gained by education.

“What prepares you to adapt? I would argue, here,” he said, referring to the auditorium full Naval War College faculty, staff and students.

“If you don’t have an intellectual underpinning, if you don’t understand the operating environment, understand your adversary, if you don’t have that as a foundation, you can be very agile, but you are just winging it,” said Berger, who holds an engineering degree from Tulane University and a master’s in international public policy from Johns Hopkins University.

The U.S. Marine Corps commandant said he is just a few months away from finalizing his design for the Corps of the future. What’s left is war-gaming and analytical work to examine how it stacks up against peer competitors.

The new design will bring change, he said. “It’s going to mean letting go, getting rid of a bunch of capabilities that we’ve had for a long time and investing in capabilities that we don’t have at all right now.”

Berger highlighted three aspects of his U.S. Marine Corps of the future. One is being a naval force. He said that’s what the nation needs from the U.S. Marines right now.

Second, Berger said the U.S. Marines need to be a “stand-in” force, as opposed to a “stand-off” force. “The [U.S.] Navy and [U.S.] Marine Corps are the masters of the close fight,” Berger said. “Ten years ago, a close fight was meters or kilometers. Now, it’s dozens of nautical miles.”

Finally, he said he supports the concept of distributed maritime operations.

“There are challenges to getting there, not the least of which are command and control and logistics,” he said. “But it gives us such advantage because we come at a threat from multiple axes.” He added that the tradition of granting decision-making authority to a ship captain, or a U.S. Marine captain in the field, is a good fit for this model.

In closing, Berger advised the audience to expect seismic shifts.

In the past, “We went after high-end, very exquisite platforms. Now we need affordable and more of them, which is a fundamental change for us. A lot more unmanned, a lot more autonomous,” he said.

“Major changes are coming. They are not very far around the corner,” Berger concluded. “I am really excited about where the [U.S.] Navy and [U.S.] Marine Corps is going.”