Teaching During COVID: Art and War Seminar Brings Museum to Students and Seniors

NEWPORT, R.I. -- A Naval War College course that uses art and poetry to study war is known for its fantastic field trips.

They include the Artillery Museum in Newport, Brown University’s Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, the USS Constitution Museum and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

But, this year, when the class coincides with a pandemic and lockdown, how does one bring art and history alive ... from home?

Cmdr. Tom Baldwin, the course’s military professor, chose to broaden the audience to embrace the experience of members of the Edward King House, a senior center in Newport, and other guests.

The King House’s Circle of Scholars program suffered its own setback this spring when on-site cultural lectures had to be cancelled due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

For the Art and War seminar on May 7, several Edward King House seniors joined Naval War College students online for a virtual tour of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and a video conference discussion of how artists have reflected the feelings and politics of their times.

“Here’s a great opportunity where we can use technology to connect with seniors and make the point that they are not forgotten,” said Baldwin, who is a member of Leadership Rhode Island and the Aquidneck Island Emergency Volunteer Alliance.

“Senior citizens are an especially vulnerable population due to COVID-19 and, as a result, are isolated from having visitors,” he said.

The tour was conducted by Tom Culora, dean of the college’s Center for Naval Warfare Studies. Culora is a professional visual artist outside of his job in academia and, in a regular year, travels to the Boston museum with the class to deliver a walking lecture on key pieces of art.

This year, his tour centered on a slide show. He used a drawing of a museum security guard to demonstrate the scale of the pieces, since the class couldn’t be in there in person.

In one example, Culora discussed “The Torn Hat” by early American artist Thomas Sully. The 1820 painting of a boy shows an earnest face framed by a tattered woven hat.

“In American art throughout the 18th and 19th century, you see the use of children as a metaphor for the moment,” Culora told the class.

“We have this intimate portrait of a young a boy, but really it’s not about this boy particularly,” he said. “He is a metaphor for America – a young, innocent America trying to try its way in the world, a little bit crude, a little bit open, a little bit vulnerable but really hopeful.”

Culora also presented Pablo Picasso’s 1963 “Rape of the Sabine Women,” calling it a depiction of Cuban Missile Crisis-era tension between the two Cold War superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union. The painting shows two warriors preparing to clash while women are being trampled under their feet.

“The allegory here is between these two opposing forces, sort of at stand off from each other, putting everyone else in peril at the bottom half of the painting,” Culora said. “These women feel the threat of this massive clash that’s happening over them that they have no control over.”

The seminar was a hit with the King House contingent.

“After we got off the Zoom call, I had one of our members call me specifically to say how impressed he was,” said Anna Matos-Mournighan, King House assistant director, adding that there was considerable interest in the opportunity. All the class slots allotted to King House members were scooped up within minutes of the invitation going out.

“This fit very well into the plan we had for getting our seniors engaged while they can’t access the building,” she said.

And the visitors were not only local.

Claire Frazier – mother of Air Force Maj. J.D. Frazier, a student in the course – joined the seminar all the way from Double Springs, Alabama, where she is a longtime art teacher at Haleyville High School.

“I thought, we’re doing a tour of the MFA and she would appreciate it,” J.D. Frazier said after the class. “And she did. She really enjoyed the tour and the take on the different paintings from around the world that we were able to pull together.”

In another adaptation this year, students were asked to present their thoughts on an art piece of their choice. Normally, they are given time to explore the Boston museum and then write a short paper on a piece of art – but they don’t have to share it with their fellow students.

The new approach was a surprise pleasure, several attendees said.

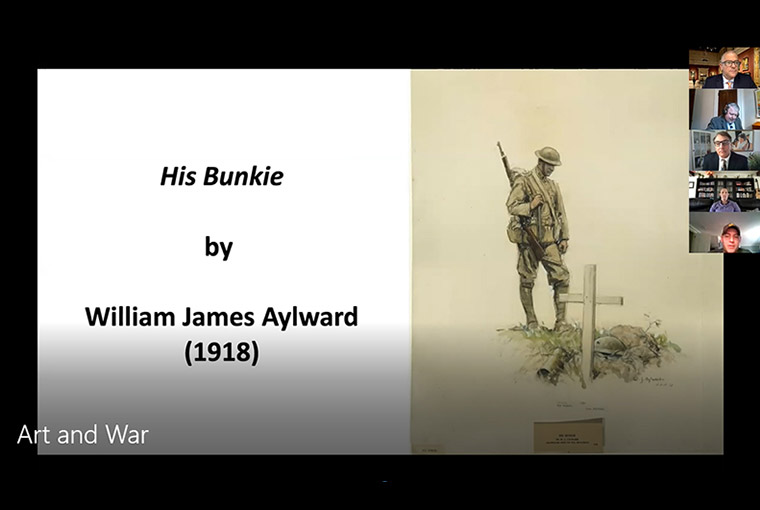

In one example, Army Capt. Jesse Edwards discussed the 1918 drawing “His Bunkie” by World War I war artist William James Aylward.

The drawing shows an American soldier staring down at the grave of his former bunkmate, his “bunkie.”

Edwards told the group that he wonders why the soldier’s face is so calm.

“I’ve stood over soldiers’ graves; I’ve stood over memorials and crosses in country. I thought the face of the soldier would be a lot more sad or distraught, as mine was on several occasions,” he said.

Edwards said he could only come up with two reasons for the artist’s choice in portraying the soldier.

“Either the hellishness of war has caused him to harden himself to the point that he didn’t have the capacity to feel. Or, his friend had found the only end to war,” he told the class.

Edwards said he was struck by the simplicity of the piece and the camaraderie he felt with the soldier.

The at-home format also allowed Rear Adm. Shoshana Chatfield, Naval War College president, to attend the class and present her thoughts on an artwork.

Chatfield discussed “The Ninth Wave,” an 1850 painting by Russian artist Ivan Aivazovsky. The piece depicts a massive wave looming over mariners who are clinging to the remains of a wrecked ship.

“We have this idea that we are going to conquer the sea, but the sea is there regardless of us. It is sheer power and force,” Chatfield said. “We may coexist with it, but we are not going to conquer it.”

The course, called Leadership and War Viewed Through the Humanities, is in its fifth year as an elective at the War College. It is co-taught by associate professor Brad Carter.

Baldwin said the topic is unusual, but powerful, in a course catalog that’s heavy on military theory and strategy.

“Human conflict is reflected in the arts, but the humanities also influence human behavior and social movements. Students are able to see how the humanities influence leaders and, with this knowledge, gain better insights into their own leadership abilities,” he said.

“This is not what you would expect at a war college. But it is absolutely important,” Baldwin said. “Because war and leadership are fundamentally human activities.”

For more on this topic, read: https://usnwc.edu/News-and-Events/News/Tough-guys-and-poetry-US-Naval-War-College-course-uses-art-and-literature-to-teach-about-war